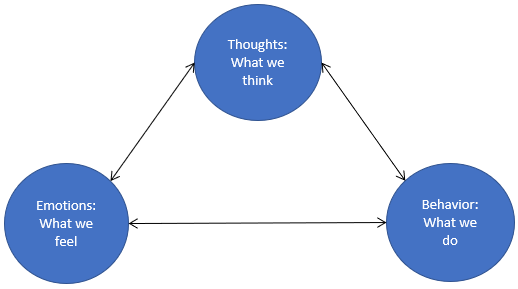

Behavioral investing looks at how investing and our emotions interact. It is not in our nature to be good investors. What causes investors to “buy low” or “sell high?” Most of us probably believe our investment transactions are based on objective information with an intense focus on achieving our goals. However, we are human. Our emotions can keep us from making objective decisions based on cold, hard facts. For example, consider the following:

· Have you bought a stock after seeing a pundit talk about it on television? (Full Disclosure: While I no longer even consider it, earlier in my life there were times I did just that. It didn’t always work out well.)

· Did you sell a stock because you were freaked out after its price dropped? (See this post for further thoughts.

· Have you bought a stock after its price started to move higher because you didn’t want to feel left out?

· Did you buy or sell a stock simply because it made you feel good?

As our last bear market bottomed during 2009’s first quarter, most investors were afraid to add new money. For those individuals, concerns about avoiding losses outweighed the potential for long-term gains. Many investors stayed on the sidelines.

On the other hand, some savvy investors realized that while the timing of the next upturn was far from certain, there were opportunities to acquire shares of high-quality companies at attractive prices that could lead to strong long-term gains.

Are We Our Own Worst Enemies?

In his book The Intelligent Investor, which was first published in 1949, Benjamin Graham, the father of value investing, said, “The investor’s chief problem – and even his own worst enemy – is likely to be himself.” These words still apply. Emotion, bias, and overconfidence are just three of the numerous behavioral traits that can negatively impact investment returns. Behavioral finance has become a recognized part of the investment lexicon.

Behavioral finance looks at psychology and emotion and seeks to explain why markets don’t always go up or down the way we expect. It has grown in importance and popularity. Daniel Kahneman and Richard Thaler won Nobel Prizes for their work in the field.

Practitioners of behavioral finance and academics alike agree that human beings are flawed, which, of course, we are. We can and do make bad decisions, particularly when confronted by uncertainty. It is hard to imagine anything more uncertain than the financial markets. Kahneman’s book Thinking Fast and Slow presents compelling examples of the ways people can make poor choices in situations despite having markedly better alternatives.

In Thinking Fast and Slow, Kahneman explores the ways in which we process information and the biases that the mental shortcuts we often use can create. He refers to two distinct thought-processing systems that we all have. System 1 can help us avoid danger and take advantage of short-term opportunities. It operates automatically and guides most of our thoughts and actions.

On the other hand, System 2 takes the slow track. It manages complex tasks such as problem-solving and other mental tasks that require concentrated effort. It is deliberate, cautious, and, unfortunately, lazy. This results in an over-reliance on System 1. It requires a conscious effort to engage System 2.

If you are familiar with Star Trek, you may understand why I equate System 1 thinking as being more akin to Captain Kirk (or later Captain Picard). System 2’s actions are more in line with the way that Mr. Spock or Commander Data think and act.

Personal Background

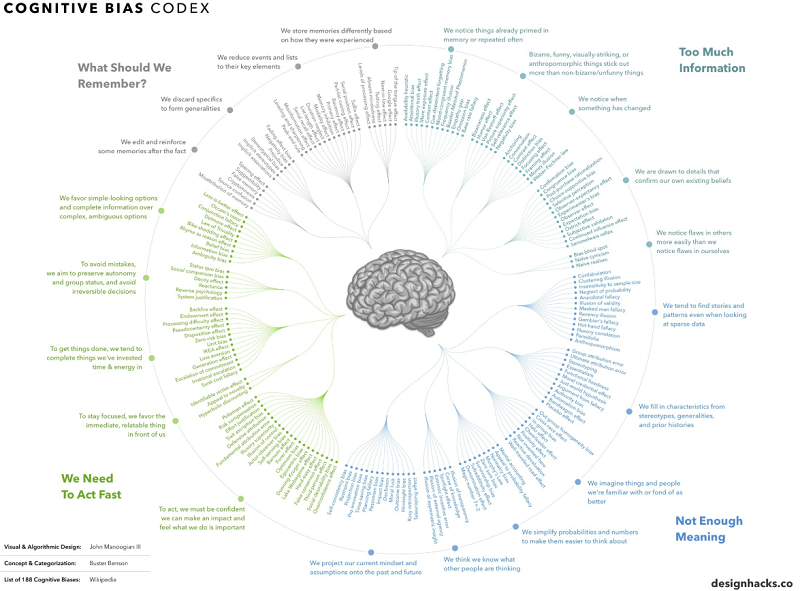

My interest in the field of Psychology goes back to college – I was originally a Psychology major at Duke University. In this blog, I shared the following graphic which shows and groups each of the 188 known cognitive biases in existence – it kind of boggles the mind to think there are that many. More recently, I spoke to the Washington, DC chapter of the American Association of Individual Investors on this topic. A copy of my March 16, 2019 presentation slide deck can be viewed or downloaded here.

The following discussion describes some common investment-related behavioral biases and suggests some ways in which they can potentially be addressed.

INVESTING AND OUR EMOTIONS – RECENCY BIAS

Recency bias is the tendency of stock market participants to evaluate their portfolio’s performance based on either recent results or their perspectives of recent results.

It is impossible to accurately forecast the market’s short-term direction. Yet investors often get caught up in the market’s daily highs and lows. Recent performance becomes a baseline for what we expect to happen in the future. In a bull market, we can easily forget that the market can decline. There is a tendency to think the market will keep going up. As a result, we keep buying while ignoring the potential downside risks. This behavioral pattern has the perverse effect of increasing a portfolio’s inherent risk. All too often it also leads to panic selling when the market reverses course.

On the other hand, when the market declines, we can become convinced that it will never rise again. In the most extreme case, we may want to liquidate our portfolios and stick the money under a mattress. Recency bias tells us the market is not going back up. Of course, one day it will, and before investors realize it, they may have missed a big portion of the upswing.

The point is not that you can accurately predict the market’s short- or long-term direction – YOU CAN’T! It is important to consider that it can go up or down and plan accordingly. Rather than take a long-term perspective and consider as many factors as possible, individuals often take the easier path and focus primarily on what is happening today.

INVESTING AND OUR EMOTIONS – CONFIRMATION BIAS

Most of us like to believe we carefully gather and evaluate facts and data (both positive and negative) before making important decisions. This can be much harder to do in practice than we think. We tend to search for or interpret information in a way that confirms our preconceptions. This is otherwise known as confirmation bias.

When an investor learns about a stock from someone else and becomes intrigued by the idea, he may become a victim of confirmation bias. This is particularly likely if the investor’s research emphasizes finding sources that “confirm” the stock’s touted potential (for example, growing cash flow or earnings) is real. At the same time, he or she may largely disregard potential red flags. These can include the loss of critical customers, weakening margins, or declining market share.

One way to minimize potential confirmation bias is to intentionally seek out analysis or research that takes the opposite view. Then assess how that affects your thesis for wanting to make the investment.

INVESTING AND OUR EMOTIONS – SUNK-COST FALLACY (SCF)

Have you ever started watching a movie (or reading a book) and realized you were not enjoying watching (or reading) it and finished it anyway? If so, you may have fallen victim to the sunk-cost fallacy (SCF). When you continue to put time, energy, or money into something because you have already invested in it and refuse to cut your losses and acknowledge that you cannot recapture those “sunk costs,” you are likely under the grip of the SCF.

In financial terms, this bias refers to the concept of “throwing good money after bad.” For example, you might double down on an investment when you believe in the story behind the stock. You do this even though the business’ performance does not justify the additional capital. How can we minimize the risk of SCF? One suggestion involves taking a fresh look at a stock that works against you before committing new money. Like with confirmation bias, you should attempt to understand the point of view of those who think differently.

It’s important to assess what has caused the company’s business to lag expectations. You want to have an informed view of whether the downturn is temporary or more permanent in nature.

INVESTING AND OUR EMOTIONS – LOSS AVERSION

Loss aversion refers to our tendency to prefer avoiding losses to acquiring equivalent gains. Some studies have suggested that losses are twice as powerful, psychologically, as gains.

For example, a basic experiment shows us that many people refuse to take bets that give them a 60% chance of winning and a 40% chance of losing a dollar. This happens even though such a refusal implies an implausibly high level of risk aversion. Mr. Kahneman justifies this decision by noting that biologically our brains might process losses in the same way as threats.

When investing, we try to avoid losses – selling a stock at a loss is more painful than selling a stock for a profit. In his classic book on investing, Common Stocks and Uncommon Profits, Philip Fisher wrote, “More money has probably been lost by investors holding a stock they really did not want until they could ‘at least come out even’ than from any other single reason.”

One way we can combat this bias is to remind ourselves that when money remains tied up in a losing stock, it is keeping us from another, potentially better idea. In addition, if the losing investment is in a taxable account, selling it can also reduce your tax bill. This realization can make recognizing a loss more palatable.

INVESTING AND OUR EMOTIONS – ANCHORING

The concept of anchoring draws on our tendency to attach or “anchor” our thoughts to a reference point – even though it may have no logical relevance. For example, investors may purchase shares of companies that have fallen considerably from their recent highs, simply because their prices declined. In this case, the investor is anchoring on a stock’s recent high price. Doing so leads them to believe the lower price provides an opportunity to purchase the stock at a discount.

However, just because a stock traded at a specific price (high or low) does not necessarily mean that price was justified. There is no substitute for rigorous critical thinking when it comes to avoiding anchoring. Determine your estimate of the stock’s intrinsic value. Then compare its current price to that figure. Don’t just let market price changes guide your decision-making.

Be especially careful about which figures you use to evaluate a stock’s potential. Successful investors do not just base their decisions on one or two benchmarks. They evaluate each company from a variety of perspectives in order to derive the truest picture of the investment landscape.

INVESTING AND OUR EMOTIONS – MYOPIC LOSS AVERSION

Myopic loss aversion occurs when investors take a view of their investments that is strongly focused on the short term, leading them to react too negatively to recent losses, which may be at the expense of long-term benefits.

For example, the week of March 4 was not a good one for most investors. The S&P 500 closed lower every day of the week. Although the market’s short-term performance should have little impact on how our assets are managed, it can have an effect. Even worse, basing investment decisions on short-term market movements can cause them to deviate from their long-term investment plan.

The main driver of myopic loss aversion is frequent feedback. One way to reduce its impact is to look at how your investments perform less often. There are amusing stories about investors who simply put their unopened statements in a drawer when the market is not performing well. Some of us could never imagine doing that. But the idea could have some merit.

For example, according to Crestmont Research, if you observed the S&P 500 Index every day from 1950-2018, you would find that, historically, it closed lower about 46% of the time. Based on our analysis, over the same period, if you only check at the start of every month, the results improve, as the market falls only about 38% of the time.

If you want to increase your chances of seeing the market move higher, only check once a year. You will find the market rises a little more than seven out of every 10 years. If you look once a decade, (based on rolling 10-year periods) you will be disappointed only about 10% of the time. This last sentiment aligns well with a quote from Warren Buffett who said, “Only buy something that you’d be perfectly happy to hold if the market shut down for 10 years.”

It is certainly difficult to hold through major bear markets like those seen in the early 2000s and 2008-2009. The best approach during a downturn could be sitting on the sidelines. The problem is you don’t know for sure when to be invested and when to hold cash. Overall, the market is up meaningfully from its lows in both 2002 and 2009, so holding positions through both downturns could have potentially led to long-term gains. Try to take comfort in the market’s long-term performance. Much of what happens in the short term is simply noise.

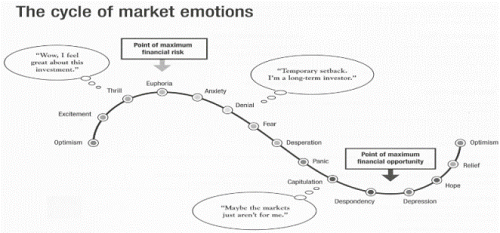

BEWARE OF THE CYCLE OF MARKET EMOTIONS

Successful investing is hard. No matter how much due diligence and analysis we perform before choosing an investment (and, afterward, while the security is held) mistakes will be made. To think otherwise would be foolhardy.

Even if an investment ultimately meets our long-term objectives, there are going to be times when its price declines. At times an investment may even drop below our cost basis, meaning there will be an unrealized loss. If there was no risk of potential (or even real) losses, stocks would not earn a risk premium relative to safer asset classes such as bonds and cash.

Many investors experience euphoria when the market is performing well and despair when it falls. The rational part of our brain tells us to “buy low and sell high.” But our emotions often encourage us to “buy high and sell low.” The following chart summarizes the different emotions an investor can experience:

As referenced in the discussion about loss aversion, the pain associated with a loss can hurt much more than the joy that comes from an equal-sized gain. This phenomenon can lead to outsized losses and smaller gains. It also can keep individuals from investing altogether. This fear has likely caused some individuals to miss the market’s rally over the past several years.

At Apprise, we certainly pay attention to the performance of securities held in client portfolios. At the same time, we strive to consistently apply our portfolio management process. Our primary focus is on the following:

· Your asset allocation (the division of your portfolio between stocks and bonds)

· Broad diversification of your holdings

· Keeping costs and fees low

· Deferring and/or eliminating taxes, when possible

We also strive to maintain an even keel whether a security goes down unexpectedly or goes up faster than we anticipated.

When investing, focus on keeping your emotions in check. While there is no foolproof method of doing so, understanding why a given security is owned and consistently applying a well-defined process can truly help.

MAKING BETTER DECISIONS

Oftentimes, we find ourselves torn between emotion and logic in our personal lives as well as when we are making investment-related decisions. Even though we may think we make most of our decisions based on logic, many are influenced by emotion. To complicate matters further, we also know people decide differently under pressure or if high risks are involved — exactly the kind of scenario experienced by investors.

Kahneman further explains these ideas in his discussion of Prospect Theory (the basis for his Nobel Prize). Prospect Theory highlights how the fear of loss or the temptation for high returns skews our rational mind. We find that investors expend too much energy trying to avoid making hard choices. Instead, they look for an informational advantage that will guarantee a “sure thing.”

We can probably improve our results by making better decisions with available information, rather than trying to find better information. Understanding the psychological behavioral components of investing can help us improve our decision-making as well.

OUTCOME VS. PROCESS

As shown in the graphic at the beginning of this discussion, there are many more behavioral biases than we have discussed in this blog. The question is, “How can we try and minimize their impact?”

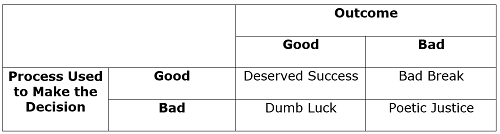

Taking a long-term perspective can help. Perhaps, the most important thing we can do is follow an investment process. Consistently following a process makes it easier to evaluate results. We tend to believe a good outcome is deserved and a bad outcome is due to tough luck. However, if we are honest with ourselves, we may realize the truth is closer to what is reflected in the following table:

Most investors focus on outcomes, not processes. They judge success on whether an investment’s value increases. While we all want to see investment gains, following a consistent process improves our chances for sustained, long-term success.

When learning of another investor’s successful investment, those that focus only on the outcome are more likely to wish they made the same investment. However, those who use a well-thought-out process are more likely to ask questions like how much effort went into the research, why they chose the investment, or attempt to learn about the investor’s overall track record.

In short, an individual outcome simply represents the final score of that one event. Success or failure was due to either skill or luck in that one instance. Over long periods, the likelihood of experiencing beneficial outcomes can be improved by employing an effective process. Put simply, we can’t just rely on luck when it comes to achieving long-term goals.

In investing, like sports, those who consistently implement a well-thought-out process are more likely to achieve success. When it comes to less desirable outcomes, process-oriented individuals will examine their methodology and try to understand where the breakdown occurred. We want to avoid making the same mistake repeatedly.

At Apprise, we have an investment process that we use to select securities for inclusion in client portfolios. We also have a specific set of rules telling us when to rebalance a portfolio. The combination of our investment process, our long-term approach to security selection, and our willingness to emphasize the long term can help us to better navigate through the market’s daily ups and downs. It also helps to minimize the impact behavioral biases may have on performance.

SUMMARY

Whether you realize it or not, the psychology of investing says you naturally have cognitive biases that could affect the way you make portfolio-related decisions. It is important that investors be aware of these potential biases and consider ways to combat them to help minimize their negative impact on performance.

Recently, Morningstar published a study called, “The Value of Advice: What Investors Think, What Advisors Think, and How Everyone Can Get on the Same Page.”

Two relevant findings were as follows:

· “Making sound financial planning decisions can generate 29% more income on average for a retiree.”

· “Behavioral coaching is the single most impactful thing an advisor can do, adding, on average, 150 basis points.” (Source Vanguard Study on Advisor Alpha.)

Interestingly, the survey of approximately 700 individual investors found that an advisor’s ability to “help [investors] stay in control of [their] emotions” ranked dead last on consumers’ rankings of what they valued from a financial advisor. This view is at least partly attributed to consumers not necessarily seeing their own behaviors as a problem in the first place.

Many of us know emotions can hamper investment returns. However, as often happens, our egos can get in the way. As a result, we may assume that others are being impacted while we are not.

If you would like to talk to us about creating a financial plan and a process to help reduce the impact of emotions on your financial health, please fill out our contact form, and we will be in touch. We can schedule a call, a virtual meeting via Zoom, or a meeting at Apprise Wealth Management’s office in Northern Baltimore County.

Follow us:

Please note that we post information about articles we think can help you make better decisions about money on Facebook and LinkedIn.

This article is not tax, legal, or other professional advice and cannot be relied upon for any purpose without consultation and advice from a retained professional.

For firm disclosures, see here: https://apprisewealth.com/disclosures/