When asked to recommend a book about investing, Megan and I have the same answer: Morgan Housel’s The Psychology of Money. The book delves into the behavioral aspects of money and investing. Morgan tells stories about how people think about money behavior. The goal is to help you be better with money. Believe it or not, there are 188 known cognitive biases in existence. I discuss some of them and include a Cognitive Bias Codex that names all 188 in this blog.

A Common Link

I (Phil) learned that Morgan would be the keynote speaker at the Maryland chapter of the Financial Planning Association’s annual symposium. I jumped at the chance to attend. In addition to my respect for Morgan as a writer, we share something in common. While our time there did not overlap, we both wrote for The Motley Fool (TMF). I was one of the managers for the Cash-King/Rule-Maker Portfolio. Not surprisingly, Morgan wrote about behavioral finance. (While listening to the Markel Group 2024 Omaha Brunch event, I was reminded of one of my favorite articles from my days with TMF – Ignore EBITDA.)

Before Morgan’s presentation, I took the opportunity to introduce myself. He noted how different the business model was when I worked there than when he did. That also impacted the type of content that was published on the website.

This week I would like to share highlights from Morgan’s presentation. Not surprisingly, it focused on The Psychology of Money.

Money and Behavior

Morgan opened by saying that doing well with money is about how you behave. Behavior is difficult to teach, which causes it to be ignored in financial education.

Think About Behavior Through Stories

If you’ve read The Psychology of Money, you shouldn’t be surprised that Morgan’s presentation centered on four stories. Interestingly, the stories were not all centered on money. The principles he discussed still apply to how we think about and act around money. (Please note that I completed some additional research so I could add more details on the stories Morgan told than I had in my notes.)

1. The Fastest Way to Rich Is to Be Slow

In this story, Morgan shared the following information about how world-class, cross-country skiers allocate their training time:

- 88.8% light intensity

- 6.4% medium intensity

- 4.8% high intensity

Is that what you’d expect? The point is you don’t want to burn out physically or psychologically. In other words, purposely go through parts of your life below your potential to make your efforts more sustainable. He also described compounding as representing returns to the power of time. Compounding is an investor’s best friend.

A Story About Compounding

While he didn’t share this in his presentation, he told this story in The Psychology of Money. It provides a great example of the value of compounding. Morgan attributes much of Warren Buffett’s success to longevity and shows how the value of compounding increases with time. Consider the following:

- Buffett began serious investing at age 10.

- He became a millionaire at age 30.

- His wealth at the time The Psychology of Money was published in 2020 was $84.5 billion.

- $84.2 billion of that amount was earned after age 50 (he was 90 in 2020).

- And $81.5 billion was earned after he qualified for Social Security in his mid-60s.

That means that over 99% of his wealth came after his 50th birthday and over 96% after he qualified for Social Security. Warren Buffett is undoubtedly a brilliant investor. However, we probably wouldn’t have heard of him if he started investing at 30 and retired at 65. Buffett’s superpower from an investing standpoint is longevity. He started investing as a child and has continued for over three-quarters of a century since then.

Buffett and Munger Had a Partner?

Do you recognize the name Rick Guerin? Probably not. Nobody in the room recognized his picture. Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger had a third partner at one time. Rick was that partner. He had a wonderful investing track record on his own. He worked with Buffett and Munger on Berkshire’s acquisition of See’s Candy in 1972 for $25 million.

What happened to Rick? He was in a hurry to get rich. He invested using leverage. During the bear market in the 70s, Rick suffered margin calls. Many of the Berkshire shares that Warren Buffett still owns once belonged to Rick.

The following quote that Morgan shared from Warren Buffett sums things up nicely:

“Charlie and I always knew that we would become incredibly wealthy. We were not in a hurry to get wealthy as we knew it would happen.

Rick was just as smart as us, but he was in a hurry.”

Morgan said, “The most important investing question is not, ‘What are the highest returns I can earn?’ It’s ‘What are the best returns I can sustain for a long period of time?’”

You can also frame this by saying that earning average returns for an above-average period leads to magic, or when it comes to investing, focus on endurance over returns.

2. The Most Valuable Financial Asset Is Not Needing to Impress Anybody.

In this section, Morgan told the story about a contest in 1968 to become the first person to sail around the world via the Three Capes single-handedly and non-stop. The competitors had to leave from a British port and return to the same place.

The Story of Donald Crowhurst

He shared the tragic story of Donald Crowhurst. Crowhurst was the least experienced contestant. He had a personal history filled with failure. To reinvent himself, he decided he would become a record-breaking sailor. Despite his inexperience, he designed his sailboat. He started off doing relatively well. Then his sailboat developed a small leak. Other problems followed.

He began thinking about dropping out of the race. If he did, what was left of his reputation would be destroyed, his business would go bankrupt, and his family could lose their home. He couldn’t give up.

What did he do? He committed fraud. He falsified his position. His logbook was fake, too. He wrote a fictional commentary making it sound like he was experiencing the conditions described in his entries. The press releases sent out about his successes were fake. The information he and his agent were sending made it look like he could win the race. The leader’s boat broke up and sank, destroying Donald’s plan to finish a close second. That individual was rescued by a passing ship. In reality, Crowhurst was “hiding” in the Atlantic. Afraid the truth would be discovered, Crowhurst realized he couldn’t return as the race’s winner. It is assumed he jumped over the side of the boat to his death. His boat was found a bit later with two sets of logbooks. One was real, the other fake.

Bernard Moitessier

Moitessier was somewhat of a French sailing legend. He broke the long-distance sailing record. Moitessier ultimately dropped out of the race and said he was sailing to Tahiti “to save his soul.” He went there, found a wife, raised a family, and lived off the land.

The Moral of the Story

Why did Morgan share this story? Think about it this way: Whenever you spend money on anything it is for one of two reasons:

- To impress people (external reasons).

- To make you happy (internal reasons).

While Crowhurst entered the race to impress people, Moitessier abandoned it as it made him happier. When working with clients on their life plans, we want to help them spend money in a way that makes them happy. Or, to help them better align their spending with what matters most to them.

Morgan closed this story with this slide:

“There are two ways to use money.

One is as a tool to live a better life.

The other is as a yardstick of status to measure yourself against others.”

3. Everyone Is a Mirror of Their Own Experiences.

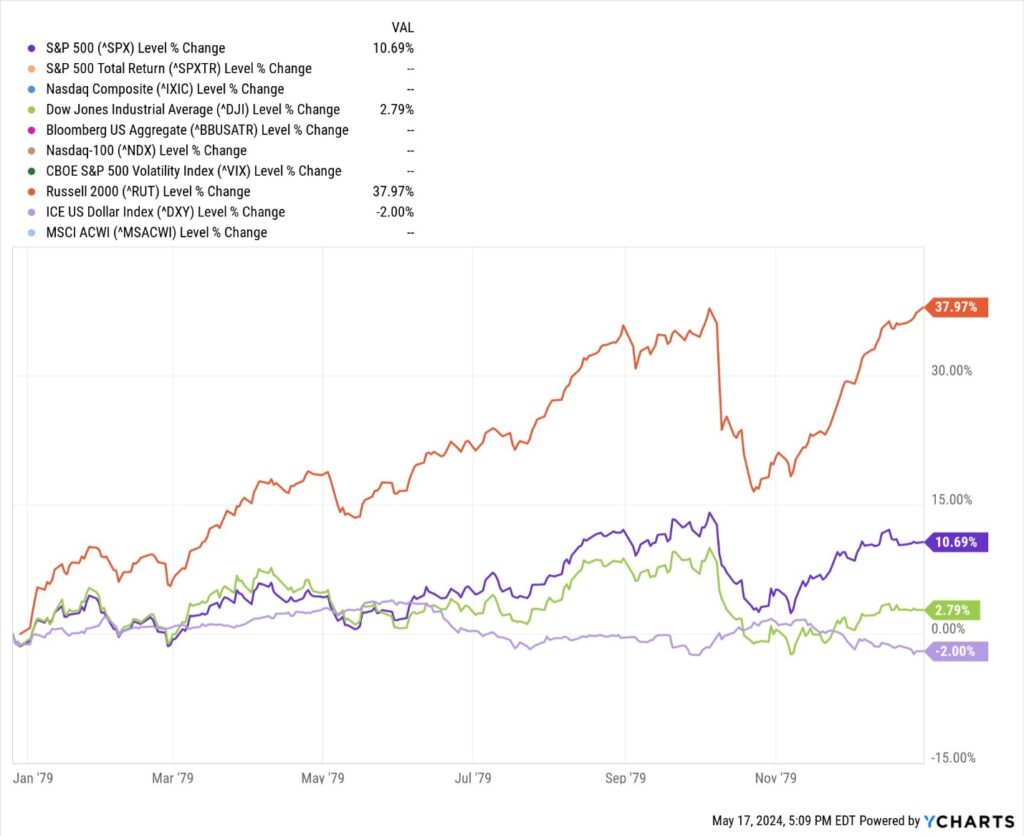

We don’t think of risk analytically. Instead, we think about it culturally. Where, when, and to whom you were born can play a big role in the ways you think about risk and investing. Consider the following two charts. The first shows the stock market’s performance in the 1950s. The second shows its performance during the 1970s.

If your first experience with investing came in the 1950s – the S&P 500 rose almost 260% – you would have a much different point of view than if your first investing experience came in the 1970s – the S&P 500 rose less than 11%.

Similarly, someone whose first memory of inflation dated to the 1970s – average annual inflation averaged 7.9% – would think differently about inflation than someone whose first memories were of the 2000s – average annual inflation averaged 2.2%. Contrast that with someone who lived through the Great Depression – inflation averaged -1.1%. In Venezuela, inflation has averaged one million percent over the last three years.

Nothing sticks with you more than what you experience firsthand, especially when you’re young.

What Can You Do About It?

We can’t change our memories or experiences. What can we do to change how we react? Morgan had some great suggestions:

- Talk to as many people as you can who have had different experiences.

- Realize that people who make different financial decisions than you are not always crazy.

In the end, Morgan noted, “Your personal experiences with money make up about 0.00000001% of what’s happened in the world and maybe 80% of how you think the world works.”

4. Risk Is What You Don’t See.

When asked for a market-related forecast, I often start by saying, “My crystal ball is both cracked and cloudy.” When I was an analyst covering the energy sector, reporters frequently asked for my prediction about oil prices. My answer would begin with, “As part of my job I’m supposed to forecast oil prices. There’s also about one number I can almost promise you won’t be the average oil price – the number I’m about to give you.” I can’t reliably predict supply and demand. I don’t know where or when a geopolitical event will occur. Nobody can predict the actions of foreign governments whose economies are largely driven by oil. I hit the number on the nose once. I attribute that quarter’s success to luck.

Morgan rates The Economist as one of the top financial publications. He shared covers from several years where the magazine predicted what would happen over the next year. A significant event occurred in each of those years. But they were not right even once. They did not forecast COVID. As for 9-11, they did not predict that either. There are countless other instances. The answer was always the same. Nobody saw what turned out to be the biggest risk over any future period.

Morgan shared this quote from Carl Richards: “Risk is what’s left over after you think you’ve thought of everything else.”

I appreciated his perspective on getting rich versus staying rich. Getting rich requires optimism. On the other hand, staying rich takes pessimism or conservatism. He said, “We should save like a pessimist and invest like an optimist.” Why? The rewards for long-term investors are extraordinary.

In sum, when it comes to finances, the only thing you can control is your behavior.

The Psychology of Money – Closing Thoughts

I hope you appreciate the wisdom Morgan shared at the FPA Symposium. When it comes to investing, it’s important to think long-term. Find others who have a different viewpoint. If you only talk to those who share your point of view, you can easily fall victim to confirmation bias.

Many of the messages shared in last week’s blog about going to the Berkshire Hathaway Shareholder meeting and this week’s have connections with life planning.

Trying to keep up with the Joneses can be dangerous. That is one of the messages that aligns so well with life planning. It’s not about building the biggest pile of money. It’s about aligning your spending with your use of capital (Time, Energy, Attention, and Money or your TEAM). Doing so can help you live your most fulfilled life.

———————————————————-

If you would like to speak with us about creating your life plan and other financial topics, including your investments, saving for college, and/or saving for retirement, please complete our contact form or schedule a call or virtual meeting via Zoom. We will be in touch.

Our practice continues to benefit from referrals from our clients and friends. Thank you for your trust and confidence.

Follow us:

Please note. We post information about articles we think can help you make better money-related decisions on Facebook and LinkedIn.

For firm disclosures, see here: https://apprisewealth.com/disclosures/